1. Introduction: The Journey from Data to Understanding

Every interaction we make in the digital realm is, in fact, data. Considering the era we live in, it’s hard to comprehend just how much data is being generated. The scale has become so vast that we now talk about large language models trained on trillions of tokens—so extensive that some are nearly capable of self-improvement through their own datasets.

But how well do we really know this data we possess? Companies today store petabytes of data—customer transactions, sensor readings, click histories, document contents… Yet if we don’t know what this data means, how it connects, or in what context it was produced, all we have is noise.

From my own experience: I’ve had the opportunity to work with databases at two different banks. What I observed was that, apart from a few core source tables, most of the summary tables created for business units lacked any clear understanding—no one knew what the columns meant or what purpose they served.

Hundreds of tables without ETL documentation or descriptive metadata. The data existed, but meaning did not.

So, does storing vast amounts of meaningless data actually benefit us? Or are we just adding to the chaos?

2. What Is Metadata?

This is where metadata—the layer that manages meaning—comes in. Metadata is the data about data; it’s what makes information interpretable, not just storable.

When you look at a table and can tell which column represents a customer’s name and which represents a transaction date, that’s thanks to metadata. Without it, data would be a shapeless heap of raw symbols.

Let’s consider a simple example:

Take a photo of your pet. Digitally, it’s just RGB pixel values.

But once you add a filename, size, capture date, or geolocation, it becomes more than a collection of pixels—it becomes meaningful content. Metadata makes that transformation possible.

At an organizational level, metadata creates a common language across hundreds of tables and millions of rows. From data analysts to software developers, from managers to AI models—metadata ensures everyone speaks the same language. It’s not just a technical detail; it’s the foundation of meaning, context, and trust.

3. Metadata Layers and the MOF

3.1 What Is MOF?

MOF (Meta Object Facility) is, simply put, the system through which we model metadata itself.

In other words, even the models that describe our data are defined by another layer of abstraction—the meta-model.

The concept of MOF was introduced by the OMG (Object Management Group), the same organization behind UML (Unified Modeling Language). MOF was created to establish a unified framework for defining different modeling languages. While UML, BPMN, and CWM may look distinct, they all rest upon the MOF foundation.

You can think of MOF as the “Big Bang theory” of modeling: everything originates from it, yet it stands above all.

Lower layers may evolve (a model might move from M1 to M2), but MOF remains the ultimate layer.

Picture the data world as a four-layered pyramid—from M0 to M3. At the bottom lies tangible data; at the top, the rules that define and govern it. Let’s look at these layers more closely.

3.2 The M0 Layer

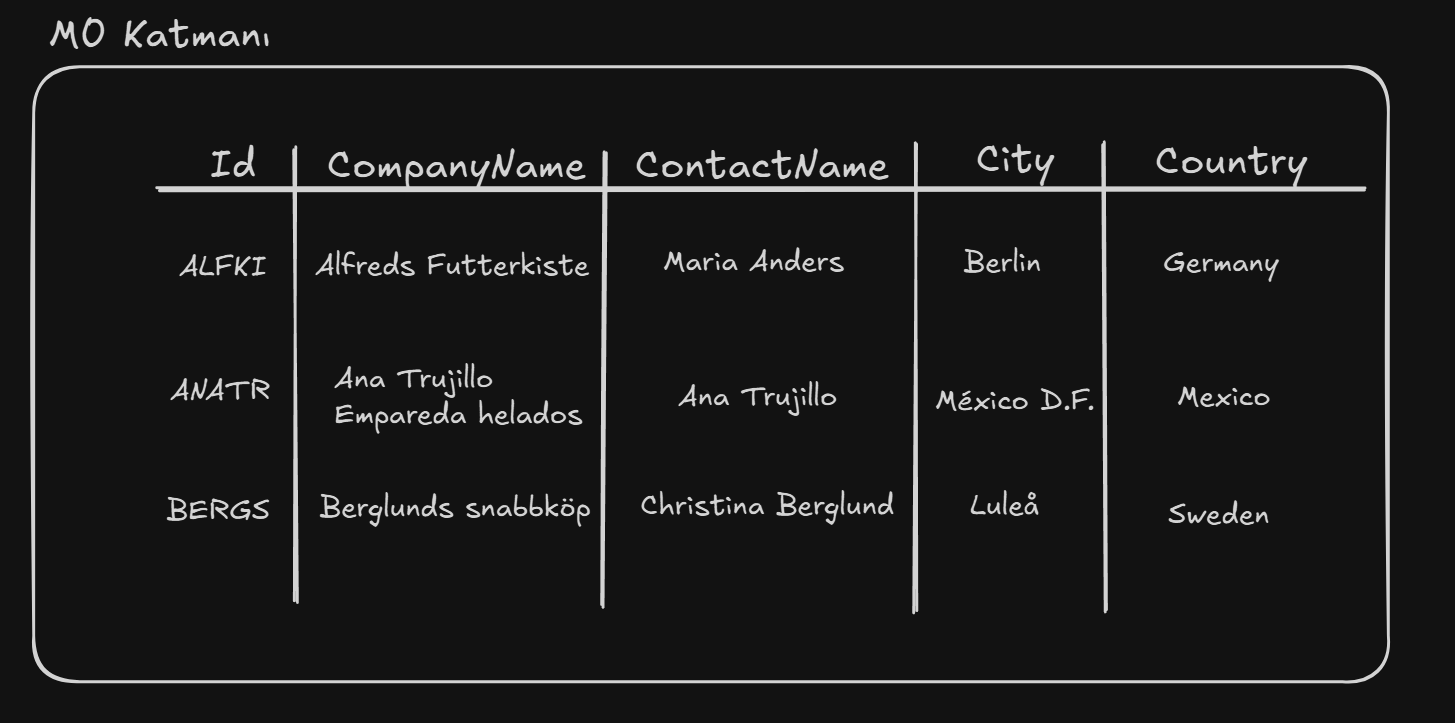

The M0 layer is the real world—the realm of raw data itself. No schema or rules exist here, only the data. The records stored in your database tables reside at the M0 level.

Observed events, measurements, documents, images, system logs—all of these are M0. Much like a language model’s tokens, M0 consists purely of unprocessed data fragments.

As shown above, the M0 layer alone doesn’t answer all questions. We can’t see the data type of CompanyName or whether it’s unique. Those answers lie one level higher, in M1.

3.3 The M1 Layer

The M1 layer defines the “contract” for the data it contains—it describes how raw data should look. This is the level of schemas rather than actual data.

For example, in the Northwind database, table designs such as the Customers table exist at M1.

Here we define which fields a table will contain, their data types, relationships between tables, and uniqueness constraints.

3.4 The M2 Layer

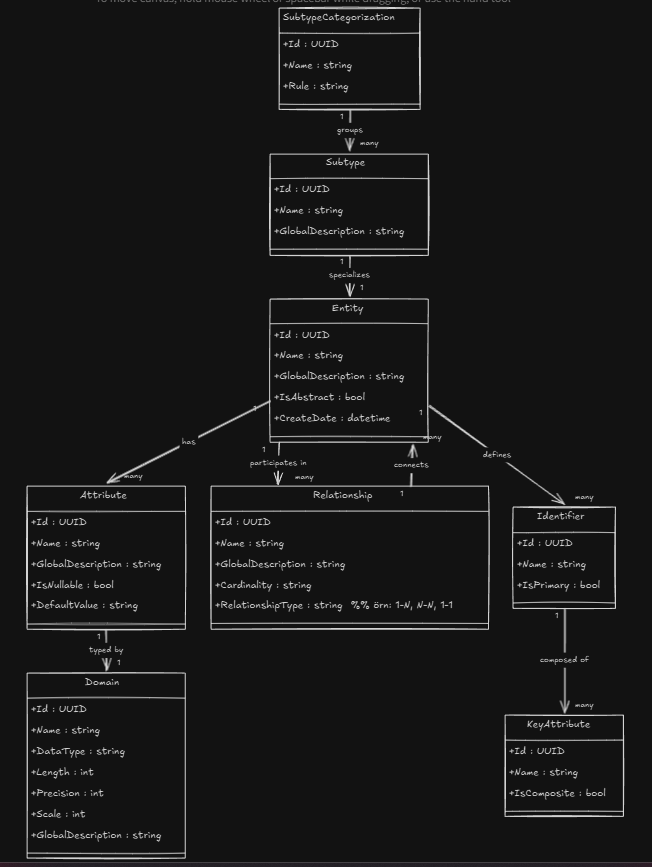

The M2 layer is the meta-model level.

At M1, we had a Customers table defined as an entity.

At M2, we define what it means to be an “entity”: what a table is, how a column is defined, and what kinds of relationships connect entities.

M2 Layer: Defines concepts such as entity, attribute, and relationship.

3.5 The M3 Layer

Finally, at the top, we reach M3—the “model of models,” or MOF itself.

This is a purely conceptual layer.

At M3, we no longer ask “What is data?” but rather “What does it mean to define data?”

Here we define not the physics of models but the laws governing those models.

4. The Building Blocks of Metadata

The constructs defined at the M2 level form the fundamental building blocks of a metadata system. Let’s go through them one by one.

4.1 Entity

An Entity is a conceptual class representing a set of objects sharing common characteristics. These can be tangible (cars, people) or abstract (companies, countries).

Each entity consists of attributes that describe its properties and relationships that connect it to other entities.

In the data world, entities usually correspond to database tables.

4.2 Attribute

An Attribute represents one of an entity’s properties.

Its value is constrained by a Domain that defines the permissible set of values.

Attributes shape both the structure and meaning of data.

4.3 Domain

A Domain defines the set of values an attribute (or group of attributes) can take.

It can be bounded (explicitly enumerated values, like country codes) or unbounded (defined by constraints, like an IBAN format).

In large organizations, domains ensure data consistency and integrity across systems.

4.4 Relationship

A Relationship expresses how one entity interacts with or depends on another.

For instance: “Each CUSTOMER may place one or many ORDERS; each ORDER belongs to exactly one CUSTOMER.”

Such relationships encapsulate the business rules that govern interactions.

4.5 Attribute Type

An Attribute Type defines the general shape and range of permissible values for a group of attributes.

For example, the “EMPLOYEE DEPARTMENT” attribute might be of type “TEXT,” meaning it contains only alphanumeric characters of limited length.

This type serves as a broad constraint above domain-specific rules.

4.6 Entity Occurrence

An Entity Occurrence represents an individual instance of an entity—a concrete manifestation of a conceptual class.

Each occurrence is defined by its specific attribute values.

4.7 Identifier

An Identifier uniquely distinguishes each occurrence of an entity.

For example, a CAR might be identified by a chassis number, engine number, or license plate.

Every entity must have at least one identifier composed of one or more Key Attributes.

4.8 Key Attribute

A Key Attribute is an attribute (or part of one) that contributes to an entity’s unique identifier.

Each key attribute corresponds to a single field but may appear in multiple identifiers.

4.9 Subtyping

Subtyping defines hierarchical specialization within entities.

A “Person” supertype may have subtypes like “Employee” or “Customer.”

It represents inheritance or classification relationships.

4.10 Subtype Categorization

Subtype Categorization organizes or groups subtype relationships under a supertype.

It distinguishes subtypes by functional or categorical differences, often used in conceptual data modeling.

4.11 Foreign Identifier

Although not explicitly defined in the original MOF references, a Foreign Identifier can be inferred as an identifier from one entity that appears as a foreign key in another—representing a unique link between related entities.

5. Why Is Metadata Management So Important?

Metadata management is not just a technical task—it’s the foundation of organizational knowledge control.

If we don’t know what information we possess, we can’t derive value from it.

As Guy Tozer states, for an organization to truly “manage data as a corporate asset,” metadata must be systematically defined and shared.

Such governance fosters transparency and prevents fragmentation.

Without centralized metadata, organizations face inconsistencies, faulty reports, and misguided decisions.

5.1 Metadata Governance and Quality

The success of enterprise-wide metadata management depends on governance—the framework that defines how data is described, who can modify it, and how changes are tracked.

At its heart lies data quality.

Many organizations mistake managing data quantity for managing data quality, but they are entirely different disciplines.

Effective metadata governance ensures:

- Consistency and accuracy.

- Centralized management of data dictionaries, business terms, and technical definitions.

- A shared reference for all stakeholders—from IT teams to analysts and business units.

This approach elevates data management from a technical activity to a strategic reflex.

6. Summary

There’s a popular saying in the information age: “Data is the new oil.”

I’d like to add a small but crucial note: “Data is the new oil if you process and store it right.”

Data is the most valuable raw material of our time, but without meaning, it’s worthless.

Metadata gives data meaning, context, and trust.

Standards like MOF ensure that meaning remains sustainable and shareable.

At the enterprise level, metadata management is not just about organizing databases; it’s about managing knowledge, preserving meaning, and maintaining coherence.

In conclusion:

Metadata is the soul of data, and MOF is the common language that defines that soul.